Blog

H. Rap Brown: An Aging Revolutionary, Legend, and Imam Facing Death by Neglect

They are killing H. Rap Brown.

Born Hubert Gerold “Rap” Brown in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in October 1943, he morphed into one of America’s leading Black freedom fighters in the 1960s. His journey into political activism began at age 15 when he organized a student walkout at the racially segregated Southern High School in Baton Rouge—then the most racially segregated city in Louisiana where Ku Klux Klan cross-burnings were as popular as LSU football. The walkout was in solidarity with students at the all-black Southern University who were protesting a wide variety of racist-inspired social conditions. The fiery young orator shut down the high school for two days and was nearly expelled because of it.

Eight years later—at a time when Gov. George Wallace was preaching throughout the state, “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”—the budding political revolutionary was in Alabama’s Black Belt, a pivotal region in the state that gave rise to the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965, where he joined local Black activists to challenge through the ballot box Wallace’s calls for white supremacy. He warned the local white-hooded KKK’ers that he was ready to “fight for the liberation of my people and anybody who tri[es] to stop me might get killed.”

A mere two years later, at age 23, Brown stood before a crowd in Cambridge, Maryland, and told them: “It’s time for Cambridge to explode, baby. Black folks built America, and if America don’t come around, we’re going to burn America down.” He urged the crowd to arm themselves, saying: “If you don’t have guns, don’t be here … you have to be prepared to die.” Cambridge erupted into flames later that evening.

It was actions like these and Brown’s rhetoric that “violence is as American as cherry pie” that caught the attention of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a racist cut in the mold of George Wallace, and prompted the director in 1967 to make Brown a target of the FBI’s COINTELPRO Program—a violent, covert operation whose purpose was to dismantle the Black Panther Party, of which Brown had been a brief member, and imprison or kill any “Black militant” who Hoover deemed to be a “threat” to America’s white power structure.

Unable to kill or silence H. Rap Brown through COINTELPRO, Republican Party leader Gerald Ford in 1968 said it was time to “slam the door” on the inspiring social justice leader and other “Black power” advocates with the passage of the “Anti-Riot Act of 1968” (more commonly known as the “Rap Brown Law“) that effectively gave corrupt law enforcement and racist prosecutors a vehicle to stifle the increasingly successful “Black Power” movement in America.

By 1971, with federal convictions, numerous arrests, and racist-inspired prosecutions against him, H. Rap Brown entered New York’s infamous “Rikers Island Jail,” proclaiming he had accepted Islam and was now a Muslim with the name Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin. This move made him an even greater target of the white, conservative political establishment in America.

For the next five years, Al-Amin was prosecuted and imprisoned by the federal government and state authorities on numerous trumped-up charges. His appeals became a fixture in the nation’s judicial system, up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Between 1976 and 1986, while under parole supervision in both New York and Georgia, Al-Amin became a non-violent Muslim activist fighting drug abuse, poverty, and violence in Black communities. In the early 1990s, Al-Amin served as an Imam and in leadership of several prominent Muslim organizations. He became president of the American Muslim Council, the first Muslim organization based in Washington, D.C., to promote Muslim issues.

Between 1990 and 1995, while living in the State of Georgia, Al-Amin founded a wide array of religious organizations, created social programs, and participated in movements designed to promote Muslim issues and end the violence crippling Black communities.

In August 1995, as federal law enforcement waged an unpublished war on the American Muslim in the wake of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, including the arrest of Al-Amin, the Imam was hounded by an FBI counter-terrorism task force and a Georgia police officer for allegedly assaulting a neighborhood resident and for an illegal firearms violation. Despite concerted efforts by both these federal and state authorities to get the resident to identify Al-Amin as his attacker, the resident refused to do so. The charge was dropped after the resident became a Muslim and joined Al-Amin’s mosque.

But Georgia law enforcement authorities refused to end their vengeful pursuit against Al-Amin. The committed Muslim peace activist, then 57 years old, was arrested in March 2000 for the killing of a Fulton County, Georgia sheriff’s deputy during a shootout with a heavily armed task force trying to serve a minor bench warrant intended for Al-Amin.

Although “at the scene” identification descriptions varied, a surviving sheriff’s deputy identified Al-Amin as the shooter. An ensuing massive manhunt led by Georgia state and local officials, with the assistance of federal authorities, resulted in the capture of Al-Amin’s in neighboring Alabama on March 16, 2000.

In March 2002, Al-Amin was convicted in Fulton County of the killing of the sheriff’s deputy and sentenced to life without parole. He was placed in the corrupt, violent Georgia prison system, where he was housed in a brutal maximum security lockdown and subjected to a continuing pattern of physical and verbal abuse by prison guards, a practice sanctioned at the highest levels of the state’s prison system.

The Georgia Supreme Court upheld Al-Amin’s conviction and sentence in November 2004.

Between 2007 and 2019, Al-Amin engaged in repeated post-conviction relief efforts to have his conviction reversed based on egregious prosecutorial misconduct and Brady violations. These efforts were rejected by the state and federal courts, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Al-Amin stated from the outset of his arrest that he was not involved in the 2000 shootout with the police and that he was in another location at the time of the shooting. The prosecution’s own evidence lends support to Al-Amin’s assertions of innocence. The wounded but surviving deputy testified that he was convinced he had wounded the assailant in the stomach, but when Al-Amin was arrested by the FBI a short time later, he did not have bullet wounds or gunpowder residue on his body.

Further, law enforcement recovered the assault rifle and the kind of ammunition that killed the sheriff’s deputy in a wooded area near an abandoned house not far from the crime scene. A blood trail led from the crime scene to the abandoned house. An ensuing search of the house led to the discovery of blood evidence; however, the blood evidence did not match Al-Amin’s, and there were no fingerprints or any other physical evidence that tied him to either the weapon or ammunition.

Al-Amin has claimed from the outset that the rifle/ammunition and other evidence were planted by former FBI agent Ron Campbell, who was assigned to Al-Amin’s case. Al-Amin charged that Campbell kicked and spat on him while making the arrest.

This former FBI agent had a sordid history of attacking Black suspects. In 1995, Campbell killed a Black man in Philadelphia while serving a warrant on the man for assaulting two police officers. The agent said he shot the man after he pulled a weapon, but an autopsy revealed the man had been shot in the back of the head.

More than two decades after his conviction Al-Amin’s supporters, led by the Justice Initiative, continue to raise these and other issues that have surfaced since his murder conviction which lend credence to his claim of innocence.

In 2007, Georgia prison officials transferred Al-Amin from state custody into the custody of the U.S. Bureau of Prisons.

The civil rights icon and Muslim activist is being held in a federal prison facility in Tucson, Arizona. He has been legally blind for years, depending upon other inmates to help him navigate prison life, and suffers from multiple myeloma.

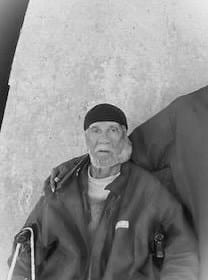

Now 81 years of age, Al-Amin has a large outgrowth on the left side of his face. A photo of the outgrowth hit various social media platforms late last year, stirring widespread outrage and prompting his family and supporters to once again take to the power of protest in an effort to have him transferred from the Tucson facility to Federal Medical Center in Butner, North Carolina.

Since the federal government has continuously pursued its vendetta against Imam Al-Amin, first announced through the “Rap Brown Law,” and with the Trump administration now in control of the executive branch, few have any faith in the prospect that Al-Amin will receive any life-saving treatment from the BOP.

The federal government, to the delight of Georgia officials, is determined to keep Al-Amin silenced in a prison cell until he dies.

Kairi Al-Amin, Almin’s son, was recently quoted by the Washington Informer as saying: “This has gone beyond wrong. This is a human rights violation.”

Shafeah M’Balia, a member of the Iman Jamil Action Network, a group fighting to secure Al-Amin’s release from prison, told the Informer shortly before a recent protest on behalf of Al-Amin that, “People are not going to idly sit while this [prison] institution conducts cruel and inhumane punishment.”

What has been done, and continues to be done, to Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin is a travesty—and despite all the white politically-inspired efforts to stifle “critical race theory,” Al-Amin is today, and will be tomorrow, a symbol of America’s sordid history of racism and the activists who sacrificed their lives and freedom in the struggle against it. Imam Jamil faced the challenges and never blinked under pressure. He will likely die in a penal facility because of corrupt police and prosecutorial misconduct—but his legacy of fighting a lawless political system and a racist social order will not die with him. As this warrior’s time ends, he should be treated humanely and given the respect owed to an icon of the civil rights movement.

Update: The Federal Bureau of Prisons inmate locator now shows Imam Jamil is located at FMC Butner Medical Center. A move that took entirely too long and occurred only after intense public pressure.

Take the first step toward protecting your freedom by contacting us now

Testimonials

John T. Floyd is Board Certified in Criminal Law By the Texas Board of Legal Specialization

Request A Confidential Consultation

Fields marked with an * are required

"*" indicates required fields